Parameterizing the Space of 3D Rotations

30 Dec 20173D medical images in the NifTI format store data from MRI acquisitions of some anatomy, like a human brain or heart. When I was a postdoc @Penn my lab was primarily interested in studying brains. Each image associates grayscale values ( in the simplest case ) to discrete coordinates $(i,j,k)$, which describe voxel locations. And for reasons best explained by NifTI FAQ it’s useful/important to align the acquired image to some other coordinate system. This alignment is stored in the image header, as a rigid motion plus an offset. Here’s a bit of NifTI documentation motivating the need to keep the alignment.

This method can also be used to represent "aligned"

coordinates, which would typically result from some post-acquisition

alignment of the volume to a standard orientation (e.g., the same

subject on another day, or a rigid rotation to true anatomical

orientation from the tilted position of the subject in the scanner).

The NifTI standard allows for orientation reversing transforms, but in this post I focus on proper rotations. These rigid motions must preserve volume and orientation; rigidity necessitates linearity. Being a geometric property, volume is preserved when this linear transformation is an isometry; which is to say, for some matrix $A$, $A A^T = I$. Moreover, orientation is preserved when $\det(A) > 0$. The intersection of all these requirements is the group of 3D rotations, usually referred to as the special orthogonal group,

\[\begin{equation*} SO(3) = \{ A \in Mat(3, \mathbb{R}) \ | \ AA^T =A^TA =I \ \& \ \det(A)=1 \}. \end{equation*}\]A final affine transform that rotates and translates image coordinates and is of the form

\[\begin{equation*} \vec{v} = A \vec{x} + \vec{q}, \quad \text{where } A \in SO(3), \ \vec{q}, \vec{x} \in \mathbb{Z}^3. \end{equation*}\]Getting to the point, $A$ isn’t what gets stored. Instead four numbers representing a unit quaternion. It seems a point in $S^3 \subsetneq \mathbb{H}$ can represent a 3D rotation. More than that, there’s a surjective homomorphism from $S^3 \subsetneq \mathbb{H}$ to $SO(3)$. Which means $S^3 \Big/\sim$ parameterizes $SO(3)$. Pretty amazing. But what’s going on here? To understand more I explore the structure and shape of $SO(3)$ in the next section.

Topology of $SO(3)$

Leonhard Euler, so long ago, discovered that $A \in SO(3)$ fixes a vector; the line through this vector is called the axis of rotation. Below is a lemma that recapitulates and generalizes this fact for rigid rotations in $\mathbb{R}^N$, for odd $N$.

Lemma. A Suppose $A \in SO(N)$ where $N$ is odd. Then $\exists \vec{n} \in \mathbb{R}^N$ so that $A \vec{n} = \vec{n}$. Equivalently, $\lambda = 1$ is an eigenvalue of $A$.

proof:

Consider $A - I$. Because $N$ is odd $\det(-(A-I)) = -\det(A-I)$. Then

\[\begin{align*} \det(A-I) & = \det(A - AA^T) = \det(A) \times \det(I - A^T) \\ & = \det(-(A^T - I)) \\ & = -\det((A-I)^T) \\ & = - \det(A-I) \\ \end{align*}\]Consequently, $\det(A-I) = 0$ which implies $\lambda = 1$ is an eigenvalue of $A$.

$\Box$

Let $A \in SO(3)$. By Lemma A $\det(A) = 1 \times \lambda_2 \lambda_3 = 1$. The immediate implication is that both of the unknown eigenvalues must be unit complex numbers and conjugates of each other; in general, the eigenvalues of any rotation are $1, \omega, \bar{\omega}$, where $\omega \bar{\omega} = 1$. In lay terms this means that $A \in SO(3)$ is a rotation of $\mathbb{R}^3$ about an axis, $[\vec{n}] \in \mathbb{RP}^2$ by some fixed angle, $\theta \in S^1$.

Since $\vec{n}$ and $\theta$ completely determine $A \in SO(3)$, it can be decomposed by a special orthogonal matrix formed from the positive frame \(\{\vec{u}, \vec{v}, \vec{n}\}\).

Dependence implies the projection

\[S^1 \times S^2 \xrightarrow{\quad pr \quad} SO(3) \quad \text{where} \quad pr(\theta, \vec{n}) = A_{\theta, \vec{n}} \in SO(3)\]is surjective. However, $pr$ is not 1-to-1. For instance $A_{0, \vec{n}} = I$ for all $\vec{n} \in S^2$. Additionally, there are a few identifications that result when one, or the other, or both coordinates in $S^1 \times S^2$ are negative. Consider $A_{-\theta, -\vec{n}}$. The positive frame for $A_{-\theta, -\vec{n}}$ is close but not the same as $A_{\theta, \vec{n}}$, because $-\vec{n}$ has the opposite orientation. The two frames differ by a permutation matrix, so the frame for $A_{-\theta, -\vec{n}}$ is

\[\begin{bmatrix} \vec{v} & \vec{u} & -\vec{n} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \vec{u} & \vec{v} & \vec{n} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -1 \\ \end{bmatrix}.\]Computing the determinant verifies the frame above is positive. Now the valid matrix decomposition for

\[A_{-\theta, -\vec{n}} = \begin{bmatrix} \vec{v} & \vec{u} & -\vec{n} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \cos \theta & \sin \theta & 0 \\ - \sin \theta & \cos \theta & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \vec{v}^T \\ \vec{u}^T \\ -\vec{n}^T \\ \end{bmatrix}.\]It’s not so apparent from the matrix decompositions of $A_{\theta, \vec{n}}$ and $A_{-\theta, -\vec{n}}$, but they’re equal. Just compute where basis elements are mapped. A similar argument shows that for $-\pi \leq \theta \leq \pi$

\[\begin{align*} A_{\theta, -\vec{n}} & = \begin{bmatrix} \vec{v} & \vec{u} & -\vec{n} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \cos \theta & - \sin \theta & 0 \\ \sin \theta & \cos \theta & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \vec{v}^T \\ \vec{u}^T \\ -\vec{n}^T \\ \end{bmatrix} \\ & = \begin{bmatrix} \vec{u} & \vec{v} & \vec{n} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \cos \theta & \sin \theta & 0 \\ -\sin \theta & \cos \theta & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \vec{u}^T \\ \vec{v}^T \\ \vec{n}^T \\ \end{bmatrix} \\ & =A_{-\theta, \vec{n}} \ . \end{align*}\]In summary, projection $pr$ has the following properties.

Identifications

- $A_{0, \vec{n}} = I$ for all $\vec{n} \in S^{2}$

- $A_{\theta, \vec{n}} = A_{-\theta, -\vec{n}}$ for $\theta \in [-\pi, \pi]$

- $A_{\theta, -\vec{n}} = A_{-\theta, \vec{n}}$ for $\theta \in [-\pi, \pi]$

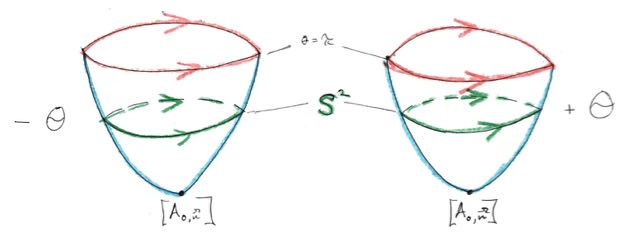

The parameter space of $SO(3)$ is $S^1 \times S^2$ under Identifications, denoted simply $S^1 \times S^2 \Big/\sim$. Not very clean though. It’s hard to imagine the shape of $SO(3)$ in this form. However, one can try by applying each identification successively to $S^1 \times S^2$. A picture will help. A heuristic image of $S^1 \times S^2$ could be a closed curve of discs ( each with proper boundary identifications to represent an $S^2$ ). In accordance with Identification $1$, the discs become smaller and smaller as the parameter on the curve approaches $0$, from the left and the right, and finally the discs degenerate to a point at $\theta = 0$. Figure #1 below is how I imagine the just described heuristic.

$S^1 \times S^2 \Big/ \sim_1$ is connected. The red discs in Figure #1 are meant to be the exact same disc, just as the points corresponding to $A_{0,\vec{n}} = I$ are the exact same point. A visualization that tried to respect the connectedness of $S^1 \times S^2 \Big/ \sim_1$ a bit more would have looked like a croissant. However, drawn as two halves separated by positive and negative angles, it is easier to see an embedded hemisphere of $S^3$ in each half.

Looking at Identifications $2$ and $3$ it’s not readily apparent – or it wasn’t to me – that they are generated by the same antipodal action,

\[S^1 \times S^2 \ni \begin{bmatrix} \theta \\ \vec{n} \\ \end{bmatrix} \longmapsto \begin{bmatrix} -1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \theta \\ \vec{n} \\ \end{bmatrix},\]on $S^1 \times S^2$. But they are.

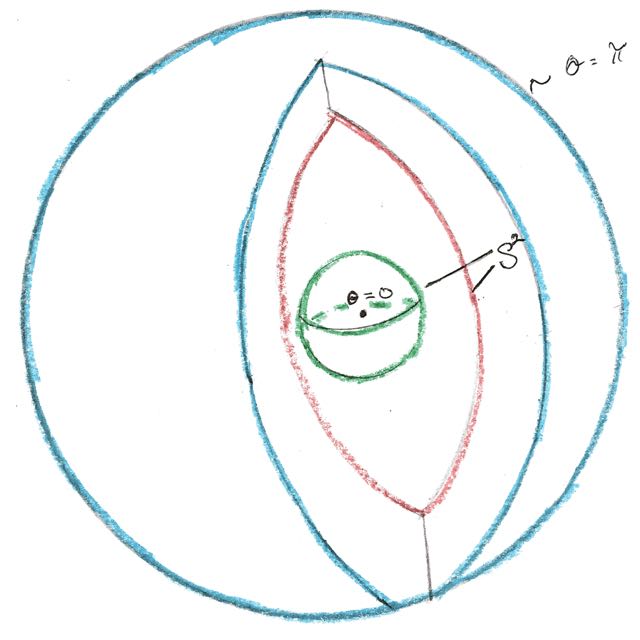

\[\begin{bmatrix} -1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \theta \\ \vec{n} \\ \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} - \theta \\ - \vec{n} \\ \end{bmatrix} \quad \text{ and } \quad \begin{bmatrix} -1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} - \theta \\ \vec{n} \\ \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \theta \\ - \vec{n} \\ \end{bmatrix}\]are Identifications $2$ and $3$, respectively. Modding out by this antipodal action is tantamount to flipping and rotating all the $S^2$ sections of say the left half, see Figure #1, and then merging the entire left half into the right half. The $S^2$ sections in the right half combine with their flipped and rotated twin in the left half resulting in a sphere. Things are different for the $S^2$ section at $\theta = \pi$. Identifications $2$ and $3$ degenerate into a single antipodal identification on that $S^2$, making it a $\mathbb{RP}^2$. The final heuristic picture when all the identifications have been applied looks like a hemisphere of $S^3$ with a $\mathbb{RP}^2$ attached at boundary, see Figure #2 below.

Figure #2 is the cell complex description of $SO(3)$. A $3$-disc (or $3$-ball), whose boundary is attached to a $\mathbb{RP}^2$. Which is precisely $\mathbb{RP}^3$.

There’s another way of visualizing $S^1 \times S^2$ I found flipping through Jeffery Week’s Shape of Space. In the chapter on product spaces $S^1 \times S^2$ is modeled as a ball in $\mathbb{R}^3$ with a hallow core; said differently, a thick sphere. The inner boundary identified with the outer boundary. The $S^2$ slices are arranged as concentric spheres; a closed curve of concentric spheres, and not of discs with boundary identifications. Reconsidering how I drew $S^1 \times S^2$ with Identification $1$, see Figure #1, I could have drawn each half as a ball in $\mathbb{R}^3$ with boundaries identified instead. A ball can be thought of as a sequence of concentric spheres which vanish at a point, the center. And it feels, to me, a bit more faithful because there are no ancillary identifications on each disc to represent the $S^2$ slices.

Application of Identifications $2$ and $3$ are no different from before; flip and rotate one half and merge it into the other. The result is a $3$-ball with antipodes of the boundary sphere identified, see Figure #3 above and Figure #4 below.

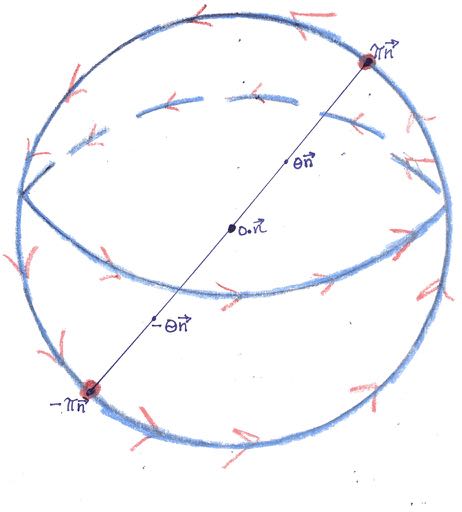

So far my technique for investigating the topology of $SO(3)$ has been to bend and stretch the parameter space $S^1 \times S^2$ and generally acted on that space in accordance with Identifications. In this way the shape/topology of $SO(3)$ and true parameter space are discovered. Loose reference was made to coordinates but no specific maps that take $S^1 \times S^2$ into the upper hemisphere of $S^3$ or the $3$-ball. Well, this is totally doable. The $3$-ball model of $SO(3)$ is particularly nice because from the association of concentric spheres $\theta \cdot S^2 \subsetneq B^3(\vec{0}, \pi)$ with spherical slices $(\theta, S^2) \subsetneq S^1 \times S^2$ the map we want

\[S^1 \times S^2 \ni (\theta, \vec{n}) \longmapsto \theta \cdot \vec{n} \in B^3(\vec{0}, \pi)\]falls out. Figure #4 below is a visualization of this projection. Inside the ball the projection satisfies Identifications, where $\theta < \pi$. As before, on the boundary ( $\theta = \pi$ ) Identifications $2$ and $3$ collapse into a single antipodal identification not satisfied by the projection. No big deal. Just impose an antipodal identification to get a homeomorphism. It’s a pretty slick way of showing $SO(3) \cong \mathbb{RP}^3$.

Lemma B below presents a map into the upper hemisphere of $S^3$ from $S^1 \times S^2$. It’s a bit more complicated, but can also be deduced from the way spheres in the upper hemisphere of $S^3$ should be arranged.

Lemma. B $$ \varphi(\theta, \vec{n}) = \Big(\vec{n} \cdot \sin \frac{\theta}{2}, \cos \frac{\theta}{2} \Big) \in S^{3} \quad \text{where} \quad \theta \in [-\pi, \pi] \text{ and } \vec{n} \in S^2 $$ takes $S^1 \times S^2$ onto the closed upper hemisphere of $S^3$. When $\lvert \theta \rvert < \pi$, $\varphi$ satisfies the same equivalences stated in Identifications. Therefore, $\mathbb{RP}^3$ is homeomorphic $SO(3)$.

proof:

Since $\cos \frac{\theta}{2} \geq 0$ for all $\theta \in [-\pi, \pi]$, $\text{Im}(\varphi)$ is contained in the the upper hemisphere of $S^3$. $\varphi$ takes the sequence of spheres

\[S^1 \times S^2 \supsetneq (\theta, S^2) \longmapsto \Big(\sin(\frac{\theta}{2}) S^2, \cos \frac{\theta}{2}\Big) \subsetneq S^3 \text{ for } 0 \leq \theta \leq \pi ,\]spherical slices cut laterally from $S^3$ by planes $z=\cos \frac{\theta}{2}$. $(0, S^2)$ gets mapped to the north pole of $S^3$ and $(\pi, S^2)$ is mapped to the equator of $S^3$. Being continuous, $\varphi$ covers all the spherical slices of $S^3$ between the equator and the north pole. $\varphi$ is onto.

Now verify that $\varphi$ satisfies the same equivalences stated in Identifications. Identification 1 states $pr(0, \vec{n}) = I$. Similarly, $\varphi(0, \vec{n}) = (\vec{0}, 1)$ for all $\vec{n} \in S^{2}$.

Identification 2 states $pr(\theta, \vec{n}) = pr(-\theta, -\vec{n})$. The same holds for $\varphi$.

\[\begin{align*} \varphi(-\theta, -\vec{n}) & = \Big( -\vec{n} \cdot \sin(-\frac{\theta}{2}),\ \cos(-\frac{\theta}{2})\Big) \\ & = \Big(\vec{n} \cdot \sin \frac{\theta}{2},\ \cos \frac{\theta}{2} \Big) \\ & = \varphi(\theta, \vec{n}). \\ \end{align*}\]Identification 3 states $pr(-\theta, \vec{n}) = pr(\theta, -\vec{n})$. The same holds for $\varphi$.

\[\begin{align*} \varphi(-\theta, \vec{n}) & = \Big( \vec{n} \cdot \sin(-\frac{\theta}{2}),\ \cos(-\frac{\theta}{2})\Big) \\ & = \Big( - \vec{n} \cdot \sin \frac{\theta}{2} ,\ \cos(\frac{\theta}{2})\Big) \\ & = \varphi(\theta, -\vec{n}). \\ \end{align*}\]The only wrinkle is on the equatorial $S^2$. As before, on the boundary ( $\theta = \pm\pi$ ) Identifications $2$ and $3$ collapse into a single antipodal identification not satisfied by $\varphi$. Imposing the antipodal identification on the boundary $S^2$, produces $\mathbb{RP}^3$.

$\Box$

A Segue

So what do we have. After interrogating the structure of special orthogonal matrices we learned that they are completely determined by data in $S^1 \times S^2$ up to Identifications. Manipulating heuristic visualizations of $S^1 \times S^2$ in accordance with Identifications yielded the topology of $SO(3)$, without any presumptions about its shape. $\mathbb{RP}^3$ is the true parameter space of $SO(3)$.

Depending on the application it might be enough to proxy $SO(3)$ with $\mathbb{RP}^3$. At issue would be the cost of computing $pr(\theta, \vec{n}) = A_{\theta, \vec{n}}$ from a presumed parameterization of $\mathbb{RP}^3$ that, say, utilizes coordinates in the open upper hemisphere of $S^3$. In establishing the topology of $SO(3)$ no direct parametrization fell out. However, it’s possible to put coordinates on $SO(3)$. In the next and final section I use a bit of representation theory to do this.

The Action of $SU(2)$ on $\mathfrak{su}(2)$

The group of rotations in $2$-dimensions, $SO(2)$, looks like $S^1$. Indeed, they are homeomorphic via

\[\theta \longmapsto \begin{bmatrix} \cos \theta & -\sin \theta \\ \sin \theta & \cos \theta \\ \end{bmatrix}.\]Amazingly, the map shown above doubles as a group isomorphism. Implicit in that statement is $S^1$ is a group. Furthermore, one can think of $\theta \in S^1$ acting on vectors $v \in \mathbb{R}^2$ via the rotation matrix associated to $\theta$. Now, $S^2$ has no group structure because it does not carry a non-vanishing vector field. In fact, no even dimensional sphere, $S^{2n}$, does. There’s a proof in Allen Hatcher’s Algebraic Topology, see Theorem 2.28. The proof is an application of Brouwer’s notion of degree for maps \(S^n \rightarrow S^n\). If $S^{2n}$ was a group, the left and right group actions would generate diffeomorphisms, from which non-vanishing vector fields could be extracted; see proposition 5.1.1. Okay. So there’s that. But there is hope for $S^3$. Consider the matrix group

\[SU(2) = \Big\{ \begin{bmatrix} a & b \\ c & d \\ \end{bmatrix} \in GL(n,, \mathbb{C}) \quad \Big\vert \quad AA^{\dagger} = A^{\dagger} A = I \Big\}.\]The condition $AA^{\dagger} = I$ in terms of the elements is

\[\begin{align*} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \\ \end{bmatrix} &= \begin{bmatrix} \lvert a \rvert^2 + \lvert b \rvert^2 & a\bar{c} + b\bar{d} \\ c\bar{a} + d\bar{b} & \lvert c \rvert ^2 + \lvert d \rvert ^2 \\ \end{bmatrix}. \end{align*}\]The constraint on the off-diagonal elements is equivalent to orthogonality of $(c\ d)$ and $(a \ b)$. So, we can choose $c = -\bar{b}$ and $d = \bar{a}$; therefore the definition of $SU(2)$ reduces to

\[SU(2) = \Big\{ \begin{bmatrix} a & -\bar{b} \\ b & \bar{a} \\ \end{bmatrix} \ \Big\vert \ \lvert a \rvert^2 + \lvert b \rvert ^2 = 1 \text{ for } a,b \in \mathbb{C} \Big\}.\]What pops out immediately is that $S^3$ exactly parameterizes $SU(2)$; $S^3$ can be equipped with the group structure of $SU(2)$. In order to define a proper action of $A \in SU(2)$ on vectors in $\mathbb{R}^3$ it’s necessary to introduce $\mathfrak{su}(2)$, the lie algebra of $SU(2)$.

Lemma. C The lie algebra of $SU(N)$, denoted $\mathfrak{su}(N)$, is the space of skew-Hermitian matrices. When $N=2$, $\mathfrak{su}(2)$ is a $3$-dimensional real vector space with basis $$ e_1 = \begin{bmatrix} i & 0 \\ 0 & -i \\ \end{bmatrix} \quad e_2 = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & -1 \\ 1 & 0 \\ \end{bmatrix} \quad e_3 = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & i \\ i & 0 \\ \end{bmatrix}. $$

proof:

By definition, $\mathfrak{su}(N)$ is the tangent space of $SU(N)$ at $I$, the identity. So, let $A(t) : (-\epsilon, \epsilon) \longrightarrow SU(N)$ be a curve such that $A(0) = I$ and $\frac{\partial A}{\partial t}(0) = B$, some complex $N \times N$ matrix. Take the derivative of $I = A(t)A(t)^{\dagger}$ at $t=0$.

\[\begin{align*} 0 &= \frac{\partial A}{\partial t}(0) A^{\dagger}(0) + A(0) \frac{\partial}{\partial t} A^{\dagger}(0) \\ &= B \cdot I + I \cdot B^{\dagger} \\ & \Longrightarrow B = -B^{\dagger} \end{align*}.\]Then,

\[\mathfrak{su}(N) = \Big\{ B \in Mat(N, \mathbb{C}) \ \Big\vert \ B = -B^{\dagger} \Big\}.\]The skew-Hermitian matrix condition on $\mathfrak{su}(2)$ matrices leads directly to the general form

\(\begin{bmatrix} i a & -c + i b \\ c +i b & -ia \\ \end{bmatrix} = a\cdot e_1 + c \cdot e_2 + b \cdot e_3 \quad \text{here } a,b,c \in \mathbb{R}\)

$\Box$

Consider the conjugation action of $SU(2)$ on itself. Differentiating this action gives exactly the action of $S^3 \cong SU(2)$ on vectors in a $3$-dimensional real vector space, the lie algebra $\mathfrak{su}(2)$, which we seek. Letting $\nu \in \mathfrak{su}(2)$, the action is

\[A \cdot \nu = A^{\dagger} \nu A \quad \text{for } A \in SU(2).\]It may not look like it but the action is an isometry ( a rotation ) of $\mathfrak{su}(2)$. Suppose $v,w \in \mathfrak{su}(2)$. Then by properties of the trace

\[\langle A \cdot v, A \cdot w \rangle = \frac{1}{2}Tr(A^{\dagger}vAA^{\dagger}w^{\dagger}A) = \frac{1}{2}Tr(A^{\dagger}vw^{\dagger}A) = \frac{1}{2}Tr(vw^{\dagger}) = \langle v, w \rangle.\]Okay. So the action is orthogonal; but does it preserve orientation? With the help of SymPy, a wonderful symbolic manipulation library, it’s possible to explicitly compute a matrix representation of the $ SU(2)$ action on all of $\mathfrak{su}(2)$. For $a^2 + b^2 + c^2 + d^2 = 1$ the matrix is

\[B = \begin{bmatrix} a^2 + b^2 - c^2 - d^2 & 2ad + 2bc & -2ac + 2bd \\ -2ad + 2bc & a^2 - b^2 + c^2 - d^2 & 2ab + 2cd \\ 2ac + 2bd & -2ab + 2cd & a^2 - b^2 - c^2 + d^2 \\ \end{bmatrix}.\]The determinant computed with the SymPy api is shown in the listing below.

In [51]: f = a**2 + b**2 + c**2 + d**2

In [52]: factor(B.det()).subs(f, 1) == 1

Out[52]: True

So yes. The action preserves orientation. The SymPy api can also verify orthogonality for us:

In [337]: factor(simplify(B * B.transpose())).subs(f,1)

Out[337]:

Matrix([

[1, 0, 0],

[0, 1, 0],

[0, 0, 1]])

In [338]: factor(simplify(B.transpose() * B)).subs(f,1)

Out[338]:

Matrix([

[1, 0, 0],

[0, 1, 0],

[0, 0, 1]])

If it wasn’t clear, $B \in SO(3)$. Indeed, the action of $S^3 \cong SU(2)$ on $\mathfrak{su}(2)$ generates a homomorphism from $S^3 \cong SU(2)$ onto $SO(3)$. A bit more work and it’s possible to show that the homomorphism is surjective. Earlier it was shown that each rotation of $\mathbb{R}^3$ is completely determined by some axis $\vec{n}$ and an angle of rotation $\theta$. Let $\vec{n} = b \cdot e_1 + c\cdot e_2 + d\cdot e_3 \in \mathfrak{su}(2) \cong \mathbb{R}^3$ and $a = \cos \theta$ encode the rotation angle. Again with SymPy, verify $B \vec{n} = \vec{n}$.

In [340]: simplify(B * Matrix([[b],[c],[d]])).subs(f, 1)

Out[340]:

Matrix([

[b],

[c],

[d]])

That is to say there’s always an $A \in SU(2)$ which generates a rotation by a given angle $\theta$ and a given line through the origin in $\mathbb{R}^3$. Therefore, the homomorphism from $S^3$ to $SO(3)$ is onto.

And there we have it! The unnamed epimorphism from $S^3 \cong SU(2)$ to $SO(3)$ provides a way to build, via coordinates on $S^3$, a direct parameterization of $SO(3)$.

One Last (very small) Note About the Topology of $SO(3)$

All the entries in $B$ from above are homogeneous polynomials of degree $2$, so it follows that $\pm A \in SU(2)$ generate the same action. The significance of which is $S^3$ is a $2$-fold covering space of $SO(3)$. I’m sure there is more to say about that, but for the moment I’ll end here.